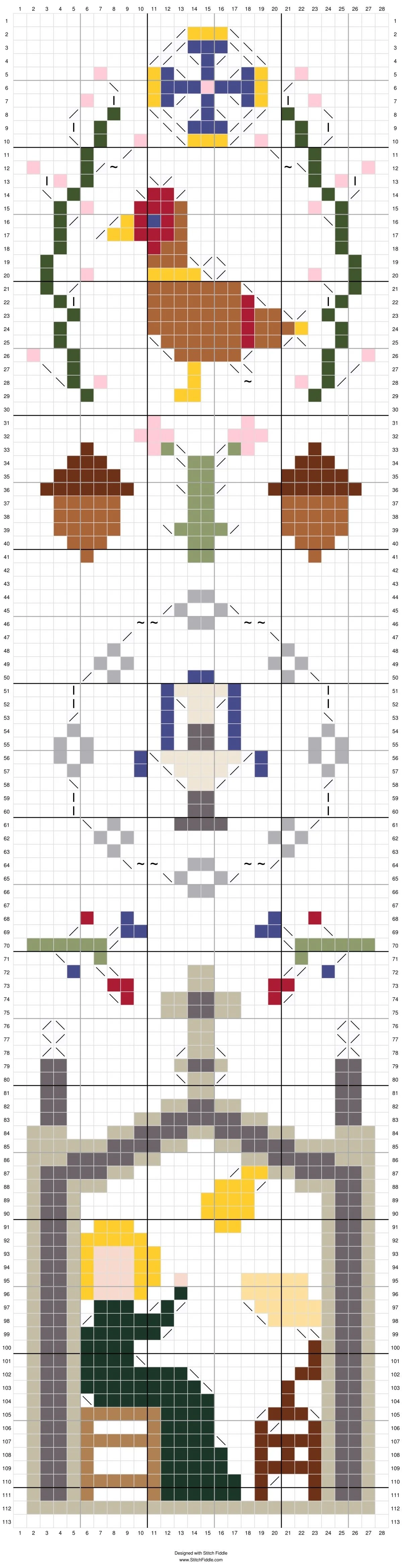

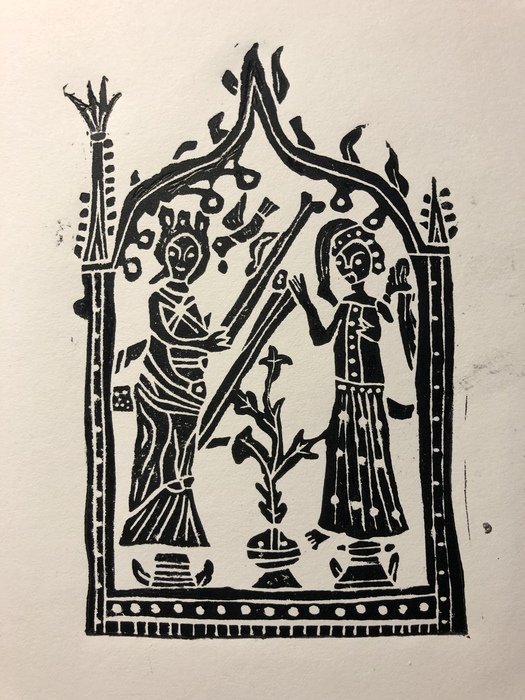

Ellen Siebel-Achenbach has created another medieval badge embroidery sampler that we happy to be sharing with you here. The embroidered bookmark features the iconography (from top to bottom) of a Tudor rose and a pomegranate (the heraldic devices of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon) two popular saints, Saint Ursula and Saint Cecilia, and medieval proverb:

For anyone new to cross-stitch, Ellen recommends this video to help you get started. If you haven’t already, try out the Cross-stitch Sampler 1!

SAINT URSULA

Saint Ursula was a legendary virgin martyr of the fourth century. She is depicted in the original pewter badge standing on a boat, with the heads of nine virgins (here, represented in grey) between her and the crosier. The legend goes that she and eleven (or in some accounts, 11,000) virgins were returning from a pilgrimage to Rome and were murdered by the Huns in Cologne. The original pewter badge depicting this scene is from Cologne (1350-1399) and was found in Dordrecht, the Netherlands. Saint Ursula’s feast day is October 21st.

SAINT CECILIA

Saint Cecilia was a third-century virgin martyr, who has been venerated as the patron saint of music and musicians, despite her obscure association to them, since the sixteenth century. Beginning in the Middles Ages, she became increasingly represented by the motif of the organ (which some thought she invented), as depicted in the embroidered form above, of the original pewter badge. The badge was found in London, England, but its origin (1000-1599) is unknown. Her feast day is November 22nd.

MATERIALS

Aida Cotton 14ct cloth

6 Strand Cotton Floss (DMC)

Embroidery needle

Regular white thread and sharp needle

Embroidery hoop (recommended)

Scissors, pencil, and ruler

An iron

Cut felt for backing (4.5 x 15 cm)

See bottom of post for colour recommendations

PREPARATION OF MATERIALS

Iron aida cloth and felt until flat.

Set felt aside for finishing and tightly secure aida cloth on an embroidery hoop.

All stitches are worked with two strands of floss, which must be separated before threading onto needle.

TIPS WHILE EMBROIDERING

At the end of each colour/strand, be sure to leave enough length to weave the floss through the back of the stitches for fastening.

It is easiest to start in the centre of the chart and work outwards, continuing to use the threaded colour until a new strand is needed or all stitches of that colour have been completed.

FINISHING

With a pencil and ruler, mark a line about six holes in from each side of the piece and cut. Fold this in half (at three holes) and sew a hem with regular thread and sharp needle.

Using appropriate size of felt, sew backing onto the embroidered piece.

Iron until flat. Do not steam; water can cause the colours of embroidery floss to run.

Enjoy your new bookmark!

You are free to use whatever colours you have. Ellen used the following: Bright Orange-Red (606); Medium Beige Brown (741); Bright Canary (973); Bright Chartreuse (704); Medium Electric Blue (996); Very Dark Lavender (208); Very Light Dusty Rose (151); Medium Beige Brown (840); Dark Yellow Beige (3045); Pale Steel Grey (3024); Medium Yellow Green (3347); Raspberry Mauve (3687); Ultra Very Light Tan (739); Grey Blue (161); Light Emerald Green (912); Medium Rose (899); Medium Burnt Orange (900); Delft Blue (809).

Design and descriptions by Ellen Siebel-Achenbach.